The Fix

The Sentence

This sentence comes from a blogpost by a writer giving advice on how to write good ad-copy for clients.

Clients want smart writing that’s engaging and will capture their message perfectly.

Feedback

The first part of this sentence, “Clients want smart writing that’s engaging”, seems fine. But in the second part, why the future tense? Why is it “will capture” rather than just “captures”? We’re guessing that clients want their message captured now! So how about this:

Clients want smart writing that’s engaging and that captures their message perfectly.

We can probably go a bit further with this.

The writer is suggesting that clients want smart writing, engaging writing, and writing that captures their message perfectly. That’s writing with three characteristics. But what is smart writing and how is it different than writing that captures a client’s message perfectly? We’re guessing that two are not that different. So, what if we revise with

Clients want engaging writing that captures their message perfectly.

We still don’t like this sentence. It seems to us that clients want engaging ad-copy that delivers (rather than captures) a message accurately. So, how about this:

Clients want engaging ad-copy that delivers a message accurately.

Odds and Ends

Steinbeck and Lean Minimalist Prose

Generally, our focus has been to rewrite sentences using as few words as possible. But sometimes that’s not the requirement. One of Hurley the Elder’s favourite passages in literature is the first paragraph of John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row:

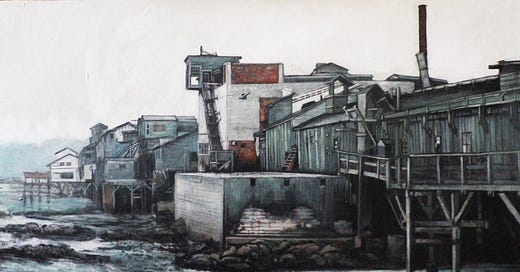

Cannery Row in Monterey in California is a poem, a stink, a grating noise, a quality of light, a tone, a habit, a nostalgia, a dream. Cannery Row is the gathered and scattered, tin and iron and rust and splintered wood, chipped pavement and weedy lots and junk-heaps, sardine canneries of corrugated iron, honky-tonks, restaurants and whore-houses, and little crowded groceries, and laboratories and flop-houses. Its inhabitants are, as the man once said, “whores, pimps, gamblers, and sons of bitches,” by which he meant Everybody. Had the man looked through another peep-hole he might have said: “Saints and angels and martyrs and holy men,” and he would have meant the same thing.

Let’s focus on the first sentence. Why does he include “in California”? If he had written “Cannery Row in Monterey is a poem, ....” isn’t the meaning the same? After all, everybody knows that Monterey is in California. Or why didn’t he write “Cannery Roy in Monterey, California is a poem ...”? Our friends who study literature suggest that sometimes the sound and rhythm of writing are more important than meaning, and maybe that’s the case here.

Now what about the list in the first sentence: "... a poem, a stink, a ..." How is Cannery Row a poem? Why isn’t it a “smell” rather than a “stink”? Or how is it a “tone”? If you look at old pictures of Cannery Row circa 1940, we think you’ll see the same thing we do, that Monterey is all those things Steinbeck lists. It’s a remarkable list.

We could examine the rest of the paragraph but you’ve probably got the point. Great novelists are careful about every word they use. More to the point, we here at Sentence Logic couldn’t carry John Steinbeck’s bags when it comes to using words to tell a story.